On January 26th, 2024, Envol Vert took part in a roundtable discussion organized by the COP collective (RESES, Climates, and Young Climate Ambassadors) at the Climate Academy, in Paris, France on the topic of climate struggles and the fight for the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Three prominent speakers stood by our side, delivering powerful speeches:

At Envol Vert, we were present as an organization fighting against deforestation, preserving biodiversity, and helping sustainable rural development and economic alternatives. We aimed to amplify the voices of the local Peruvian and Colombian communities that are part of the organization and with whom we closely collaborate.

Who are Indigenous Peoples?

While they represent more than 6% of the global population and are spread across nearly 90 countries, defining Indigenous peoples is not straightforward. The UN identifies them as follows:

“Indigenous peoples have in common a historical continuity with a given region prior to colonization and a strong link to their lands. They maintain, at least in part, distinct social, economic and political systems. They have distinct languages, cultures, beliefs and knowledge systems. They are determined to maintain and develop their identity and distinct institutions and they form a non-dominant sector of society.”

For Juan Pablo Gutierrez, this definition is an opportunity to emphasize a crucial point: Indigenous peoples were present on their territories before colonization and challenge us to face our Eurocentric world view. Thus, the symbol of the year 1492 needs to be revised: it is not only about the “discovery of America” as we often refer to it, but also about the “discovery of Europeans” by the indigenous peoples of the American continent.

For him, what truly defines Indigenous peoples is diversity. As a member of the Yukpa, people, one of the 115 Indigenous peoples identified in Colombia, he feels entitled to speak for the Yukpa, but certainly not for all indigenous peoples worldwide. Indigenous peoples, indeed, are not a ‘monolithic bloc,’ as he puts it, but rather numerous peoples (not ‘communities’) each with their own culture, organizational system, principles of justice, language, cosmogonies, and beliefs… And this is just in Colombia, with 115 distinct peoples.

As Mutesi Van Hoecke reminds us, Indigenous peoples are not only found in the Amazon, but all over the planet: from the Arctic to the Pacific, through Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The UN thus counts more than 5,000 distinct peoples.

Mutesi Van Hoecke sheds light on sociological and epistemological debates concerning Indigenous peoples from the African continent. While it seems rather clear that, today, groups still settled in African territories and living according to the rites and cultures specific to their people are indeed ‘indigenous,’ the question becomes more complex for ‘uprooted’ groups. With slavery and the transatlantic slave trade, numerous Indigenous peoples were deported from their lands, including to other continents. Are their descendants still ‘Indigenous’? The question remains open and should be approached keeping in mind one of the key elements in the definition of Indigenous peoples, namely self-determination. In fact, it is on behalf of this principle that the definition of indigenous peoples has deliberately been omitted from international law and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

What’s the Connection to Environmental Struggles?

UNESCO reports that Indigenous peoples protect nearly 80% of global biodiversity. Indeed, their ways of life generally prioritize sustainable management of their resources and environment.

Juan Pablo Gutierrez, however, cautions that it is often easy to reduce Indigenous peoples to their role as guardians of nature. Yet, this is not their role; it is simply the direct consequence of their healthy relationship with their environment and their struggles to keep management rights over their territories.

These management rights are the subject of demarcation procedures advocated by Brazilian Indigenous peoples supported by the Jiboiana organization. The principle of demarcation (demarcação) has been provided for in the Brazilian Constitution since 1988 and involves delineating a part of the territory within which Indigenous peoples have management rights.

Demarcated territories, autonomously managed by Indigenous peoples, not only represent the recognition of the existence and culture of these peoples, but they also mechanically benefit from such a status as they end up protected by the rightful owners of the territory. Indeed, no extensive agriculture, clear-cutting, or slash-and-burn deforestation is likely to affect these lands.

None? Except when those practices are illegally happening, as we, at Envol Vert, keep denouncing. Indeed, within a coalition of 11 environmental preservation organizations and Indigenous peoples’ associations, we have taken legal action against the French Casino Group and its double standards following an investigation concluded in 2020. Among its subsidiaries one can find Naturalia in France, a supermarket chain certified as a B Corp and whose slogan is “Responsibility and Transparency,” but also the Grupo Pão de Açúcar (GPA) in Brazil, and Exito in Colombia, whose beef products sold in their stalls, or at least part of them, are sourced from illegal deforestation that sometimes encroaches on indigenous territories. In doing so, the Casino Group would fail to fulfil its duty of vigilance.

The stakes of this trial are enormous and mobilize a large number of actors from civil society. Juan Pablo Gutierrez strongly reminds us that for Indigenous peoples, ‘activism is not a weekend hobby, but a matter of survival‘.

Colonialism and the Destruction of Life

For the speakers, the link between the excesses of colonialism and the destruction of life is undeniable. Indeed, colonialism marked the beginning of a relationship of dominance and dependence that is still maintained today through capitalist ties exploiting raw materials, mineral resources, etc.

Juan Pablo Gutierrez reminds us that Indigenous peoples have often been ‘saved’ at their expense: first in the name of Christianity, then civilization, then progress… and today in the name of economic development. For him, contemporary capitalism is just a continuation of colonialism that has, in essence, never truly ceased.

For the Jiboiana association, it is crucial, as a Western organization, never to unilaterally decide on support actions in favour of Indigenous peoples: this is the best way to avoid falling into the “White Savior” syndrome, derived from paternalism and inheriting from colonialism. Today, numerous sociological studies demonstrate the risks associated with these modes of operation: reinforcing dependence and loss of autonomy, community breakdown, generating tensions…Thus, any support action must be built on the initiative of the supported peoples, according to their needs all while respecting their culture. This co-construction methodology constitutes a guiding principle for us, at Envol Vert. Each project is built and evolves with farmer groups, local associations, or cooperatives.

In addition, Mutesi Van Hoecke wished to emphasize a form of hypocrisy she encountered within environmental activist circles, where although individuals were particularly dedicated to preserving the planet, they showed much less empathy for associated social issues… and even exhibited racist behaviours and remarks.

Yet, it is essential to be coherent. We all still remember the slogan ‘end of the world, end of the month, same fight.’ Indeed, fighting for the environment while being insensitive to social issues, both in the addressed territories and among the individuals involved in the struggles, neither allows us to grasp the magnitude of the challenges nor to mobilize widely and sustainably for the cause.

Indigenous Peoples: A Solution for Building the Society of Tomorrow

Climate disruption and the collapse of biodiversity have already begun. 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded.

“The average of the twelve months is significantly higher than those of previous record years, 2016 and 2020, which were already 1.29°C and 1.27°C higher than pre-industrial levels, according to the WMO,” reports Le Monde.

Numerous climate disasters and the increasing frequency of their occurrence make the consequences of this disruption increasingly visible and concrete. Furthermore, accessing mineral resources and fossil fuels will become increasingly difficult.

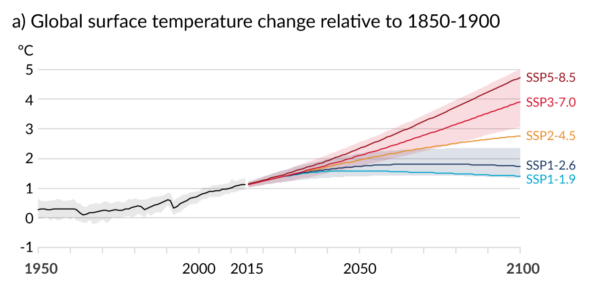

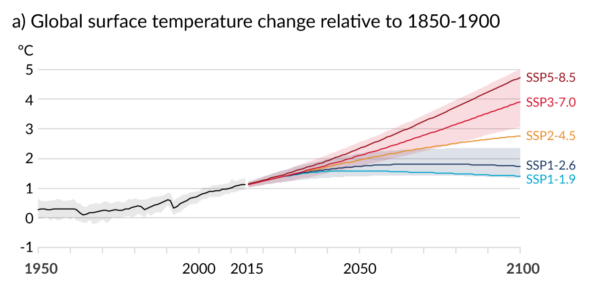

The IPCC consolidates scientific studies to present several scenarios based on our societies’ ability to reduce our carbon emissions levels.

To limit the impacts of climate disruption and maintain them at a level where our current Western lifestyles are not threatened, the COP21, in 2015, set a goal to limit global warming between 1.5°C and 2°C by 2100, in adequation with scenario SSP1-2.6.

In 2023, we have nearly reached 1.45°C already. We are ahead of the scenario by 77 years. Therefore, the preferred scenario unfortunately has a high chance of not being achieved.

Graph from the 6th IPCC report

The IPCC is not the only one producing scenarios. In France, ADEME has also worked on 4 prospective scenarios to imagine the evolution of our lifestyles (cf. Transition(s) 2050). There are also attempts in collapsology that question the post-collapse era (for example, ‘Another end of the world is possible: living the collapse (and not just surviving it)‘, by Pablo Servigne, Raphaël Stevens, and Gauthier Chapelle). Finally, associations also offer the general public reflections to make these inevitable tomorrows more desirable, such as New Narratives Collage.

Today, this question is at the heart of debates: what will tomorrow’s society look like in the context of climate disruption and biodiversity collapse?

To answer this critical issue, and to attempt to provide solutions for adapting to and mitigating environmental risks, we may have among us more than 5,000 sources of inspiration: Indigenous peoples.

On January 26th, 2024, Envol Vert took part in a roundtable discussion organized by the COP collective (RESES, Climates, and Young Climate Ambassadors) at the Climate Academy, in Paris, France on the topic of climate struggles and the fight for the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Three prominent speakers stood by our side, delivering powerful speeches:

At Envol Vert, we were present as an organization fighting against deforestation, preserving biodiversity, and helping sustainable rural development and economic alternatives. We aimed to amplify the voices of the local Peruvian and Colombian communities that are part of the organization and with whom we closely collaborate.

Who are Indigenous Peoples?

While they represent more than 6% of the global population and are spread across nearly 90 countries, defining Indigenous peoples is not straightforward. The UN identifies them as follows:

“Indigenous peoples have in common a historical continuity with a given region prior to colonization and a strong link to their lands. They maintain, at least in part, distinct social, economic and political systems. They have distinct languages, cultures, beliefs and knowledge systems. They are determined to maintain and develop their identity and distinct institutions and they form a non-dominant sector of society.”

For Juan Pablo Gutierrez, this definition is an opportunity to emphasize a crucial point: Indigenous peoples were present on their territories before colonization and challenge us to face our Eurocentric world view. Thus, the symbol of the year 1492 needs to be revised: it is not only about the “discovery of America” as we often refer to it, but also about the “discovery of Europeans” by the indigenous peoples of the American continent.

For him, what truly defines Indigenous peoples is diversity. As a member of the Yukpa, people, one of the 115 Indigenous peoples identified in Colombia, he feels entitled to speak for the Yukpa, but certainly not for all indigenous peoples worldwide. Indigenous peoples, indeed, are not a ‘monolithic bloc,’ as he puts it, but rather numerous peoples (not ‘communities’) each with their own culture, organizational system, principles of justice, language, cosmogonies, and beliefs… And this is just in Colombia, with 115 distinct peoples.

As Mutesi Van Hoecke reminds us, Indigenous peoples are not only found in the Amazon, but all over the planet: from the Arctic to the Pacific, through Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The UN thus counts more than 5,000 distinct peoples.

Mutesi Van Hoecke sheds light on sociological and epistemological debates concerning Indigenous peoples from the African continent. While it seems rather clear that, today, groups still settled in African territories and living according to the rites and cultures specific to their people are indeed ‘indigenous,’ the question becomes more complex for ‘uprooted’ groups. With slavery and the transatlantic slave trade, numerous Indigenous peoples were deported from their lands, including to other continents. Are their descendants still ‘Indigenous’? The question remains open and should be approached keeping in mind one of the key elements in the definition of Indigenous peoples, namely self-determination. In fact, it is on behalf of this principle that the definition of indigenous peoples has deliberately been omitted from international law and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

What’s the Connection to Environmental Struggles?

UNESCO reports that Indigenous peoples protect nearly 80% of global biodiversity. Indeed, their ways of life generally prioritize sustainable management of their resources and environment.

Juan Pablo Gutierrez, however, cautions that it is often easy to reduce Indigenous peoples to their role as guardians of nature. Yet, this is not their role; it is simply the direct consequence of their healthy relationship with their environment and their struggles to keep management rights over their territories.

These management rights are the subject of demarcation procedures advocated by Brazilian Indigenous peoples supported by the Jiboiana organization. The principle of demarcation (demarcação) has been provided for in the Brazilian Constitution since 1988 and involves delineating a part of the territory within which Indigenous peoples have management rights.

Demarcated territories, autonomously managed by Indigenous peoples, not only represent the recognition of the existence and culture of these peoples, but they also mechanically benefit from such a status as they end up protected by the rightful owners of the territory. Indeed, no extensive agriculture, clear-cutting, or slash-and-burn deforestation is likely to affect these lands.

None? Except when those practices are illegally happening, as we, at Envol Vert, keep denouncing. Indeed, within a coalition of 11 environmental preservation organizations and Indigenous peoples’ associations, we have taken legal action against the French Casino Group and its double standards following an investigation concluded in 2020. Among its subsidiaries one can find Naturalia in France, a supermarket chain certified as a B Corp and whose slogan is “Responsibility and Transparency,” but also the Grupo Pão de Açúcar (GPA) in Brazil, and Exito in Colombia, whose beef products sold in their stalls, or at least part of them, are sourced from illegal deforestation that sometimes encroaches on indigenous territories. In doing so, the Casino Group would fail to fulfil its duty of vigilance.

The stakes of this trial are enormous and mobilize a large number of actors from civil society. Juan Pablo Gutierrez strongly reminds us that for Indigenous peoples, ‘activism is not a weekend hobby, but a matter of survival‘.

Colonialism and the Destruction of Life

For the speakers, the link between the excesses of colonialism and the destruction of life is undeniable. Indeed, colonialism marked the beginning of a relationship of dominance and dependence that is still maintained today through capitalist ties exploiting raw materials, mineral resources, etc.

Juan Pablo Gutierrez reminds us that Indigenous peoples have often been ‘saved’ at their expense: first in the name of Christianity, then civilization, then progress… and today in the name of economic development. For him, contemporary capitalism is just a continuation of colonialism that has, in essence, never truly ceased.

For the Jiboiana association, it is crucial, as a Western organization, never to unilaterally decide on support actions in favour of Indigenous peoples: this is the best way to avoid falling into the “White Savior” syndrome, derived from paternalism and inheriting from colonialism. Today, numerous sociological studies demonstrate the risks associated with these modes of operation: reinforcing dependence and loss of autonomy, community breakdown, generating tensions…Thus, any support action must be built on the initiative of the supported peoples, according to their needs all while respecting their culture. This co-construction methodology constitutes a guiding principle for us, at Envol Vert. Each project is built and evolves with farmer groups, local associations, or cooperatives.

In addition, Mutesi Van Hoecke wished to emphasize a form of hypocrisy she encountered within environmental activist circles, where although individuals were particularly dedicated to preserving the planet, they showed much less empathy for associated social issues… and even exhibited racist behaviours and remarks.

Yet, it is essential to be coherent. We all still remember the slogan ‘end of the world, end of the month, same fight.’ Indeed, fighting for the environment while being insensitive to social issues, both in the addressed territories and among the individuals involved in the struggles, neither allows us to grasp the magnitude of the challenges nor to mobilize widely and sustainably for the cause.

Indigenous Peoples: A Solution for Building the Society of Tomorrow

Climate disruption and the collapse of biodiversity have already begun. 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded.

“The average of the twelve months is significantly higher than those of previous record years, 2016 and 2020, which were already 1.29°C and 1.27°C higher than pre-industrial levels, according to the WMO,” reports Le Monde.

Numerous climate disasters and the increasing frequency of their occurrence make the consequences of this disruption increasingly visible and concrete. Furthermore, accessing mineral resources and fossil fuels will become increasingly difficult.

The IPCC consolidates scientific studies to present several scenarios based on our societies’ ability to reduce our carbon emissions levels.

To limit the impacts of climate disruption and maintain them at a level where our current Western lifestyles are not threatened, the COP21, in 2015, set a goal to limit global warming between 1.5°C and 2°C by 2100, in adequation with scenario SSP1-2.6.

In 2023, we have nearly reached 1.45°C already. We are ahead of the scenario by 77 years. Therefore, the preferred scenario unfortunately has a high chance of not being achieved.

Graph from the 6th IPCC report

The IPCC is not the only one producing scenarios. In France, ADEME has also worked on 4 prospective scenarios to imagine the evolution of our lifestyles (cf. Transition(s) 2050). There are also attempts in collapsology that question the post-collapse era (for example, ‘Another end of the world is possible: living the collapse (and not just surviving it)‘, by Pablo Servigne, Raphaël Stevens, and Gauthier Chapelle). Finally, associations also offer the general public reflections to make these inevitable tomorrows more desirable, such as New Narratives Collage.

Today, this question is at the heart of debates: what will tomorrow’s society look like in the context of climate disruption and biodiversity collapse?

To answer this critical issue, and to attempt to provide solutions for adapting to and mitigating environmental risks, we may have among us more than 5,000 sources of inspiration: Indigenous peoples.